I’m fascinated by issues relating to conservation of cultural objects, but most of the publicity goes to fine art conservation–if there is any at all. Friday’s disaster at the Metropolitan Museum, where a woman taking an adult education class fell on an early Picasso, The Actor, and tore a 6″ hole in the canvas, got some play in the tabloids and finally made the New York Times.

The New York Post concentrated on the question of the painting’s $130 million appraisal being shaved in half and then raised the question how could the public get so close to something so valuable. Here’s the first story which talks about the accident and the follow up story on Jan 26, noting a $65m loss of value; one of the commentors raise the question of getting close.

The Times‘s coverage started with a brief Jan 25, 2010 notice, and then a longer article on the same day by Carol Vogel about the incident, but included lots of good commentary from experts (this is what the Times is great at):

The accident recalled another human-canvas run-in involving a Picasso. In 2006 the Las Vegas casino owner Stephen A. Wynn put his elbow through “Le Rêve” (“The Dream”), a 1932 Picasso of the artist’s mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter, leaving a sizable hole that has been so artfully repaired that the untutored eye would never know such a fate had befallen it. [It was owned by Wynn at the time. pwr]

But it is difficult to compare a 1932 Picasso with one painted in 1904-5. The early canvases are more delicate and the oil paint is thinner than the enamel-based kind the artist was known to have used later in his career. And then there is the question of whether there’s only one image involved.

“The Actor” was painted when Picasso was only 23. “He was very poor, and these canvases were expensive,” said John Richardson, the Picasso biographer. He explained that if Picasso made a mistake, he couldn’t afford to throw out the canvas, but rather painted over it. “Nearly all these early canvases have something painted underneath,” Mr. Richardson said.

He added: “There are few major paintings from this period and” — at 4 feet by 6 feet — “this is one of the biggest. It’s very important.”Dealers say a painting of this scale and period could be worth well over $100 million.

It’s an image — a tall, gaunt actor, dressed in a commedia dell’arte costume, leaning out across the footlights — that has often been puzzling to viewers, Mr. Richardson said, adding, “People seem to miss out on the fact that the actor is on a stage, which is unusual.” (emphasis added; source)

So, the Times brings up the point that the earlier canvas may be multi-layered. Sadly, the Met was not forthcoming in volunteering whether the canvas was multilayer OR where the tear was. The art expert sounded a bit uncertain. (A subsequent article has Met representatives giving excuses/explanations for not publicizing these bits of information…. see below.)

I also like Vogel’s comparison at the end:

Like a gifted plastic surgeon, a seasoned restorer has many options these days and a host of materials and instruments at his disposal, even acupuncture needles. They are not used as they would be in Asian medicine, to puncture a surface, or to sew a canvas, but rather are applied from behind to keep a tear flat.

Metaphors can be very powerful in selling the public and contributors on the value of conservation. You don’t want to tell them that “enzymatic solution” is all-too-often a euphemism for spit. But I once explained to my then-employers that buying some solvents in a pharmacy wouldn’t remove scotch tape from some paper mss by comparing the varying proportions needed in removing adhesive to a “kind of chemical brinksmanship” in which the conservator might have to test solvents in different combinations and concentrations to get the most effective removal.

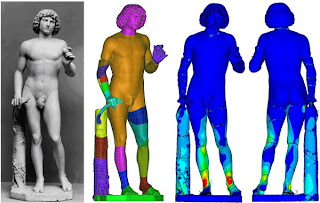

On the 27th Randy Kennedy wrote an article about conservation sometimes taking much longer than the forecast: “… two other rare mishaps at the Met in recent years have provided hard lessons about the difficulty of making broken masterpieces whole again and of predicting when they will go back on view.” (The Picasso was expected to be in time for a major show–about a year.) The Kennedy article revolved around the very long treatment and pre-treatment work being done on Tullio Lombardo’s “Adam” (at right, shown before and with two computer-generated repairs), which was damaged in 2002. The Tullio was estimated at two years, but it’s now seven and counting. Kennedy’s comments from the Ian Wardropper, chairman of the Met’s department of European sculpture and decorative arts, are interesting:

[The conservation] has also been conducted in a kind of seclusion unusual for the museum, one that in combination with the long delay has fed occasional speculation that the statue might be beyond repair. But Mr. Wardropper said that the decision to conduct the project outside public view was driven in part by his own worries that seeing images of broken sculpture could be detrimental to museumgoers’ ability to appreciate such pieces once they are repaired. And the delay, he said, has been the result of a decision to restore the statue in the most meticulous and durable way possible — an enterprise that has been hindered by the fact that few pristine life-size museum marbles like the Adam have ever shattered, so reliable technical information about restoring one is limited.

“You can do this quick and dirty,” Mr. Wardropper said. “We probably could have done it in a year, and maybe it would have held together just fine.”

The delays (and secretiveness of the Met) are raising questions, so Wardropper has some good responses. His points are legitimate, although I don’t like Wardropper’s “quick and dirty” throw-away which is dismissive and could even be seen delegitimitizing the work of other museums and conservators who don’t have large budgets (and unlimited patience of their patrons/customers). The Met is engaging in extensive research which is causing a lot of delay:

But curators and conservators, he said, decided to hold off on any rebuilding before commissioning extensive scientific studies: of adhesives, for example (much of that research was recently published by the British Museum) and of materials that could be used for pins to mend the limbs of the sculpture. (It has turned out that fiberglass or carbon fiber are better than metal because they do less damage to the marble around them.)

Conservators have also used recently developed laser-mapping technology to create a three-dimensional “virtual Adam” that is being used to piece the work back together and also to allow engineers to determine the places within the sculpture that will undergo the most stress when it is standing again.

[….] Mr. Wardropper decided along with conservators and other curators that precision was more important than speed. It helped that a large insurance settlement, the size of which the museum declined to specify, has covered most of the project. The restoration will eventually be the subject of an entire exhibition, he said, and the sculpture will be the centerpiece of a new gallery devoted to the Venetian Renaissance.

I admire Wardropper’s “precision was more important than speed” formulation, and I think this paragraph makes up for so much of the delays. And yet, one ask whether the conservators are studying the problem to death while a half-generation of art scholars have no access to the original sculpture.

I was bothered by the Met’s (and Wardropper’s) decision not to allow photographs of the damaged artwork and, although I see his point, I also found this excuse a tad lame for a semi-public institution (in the sense that it received city land, subsidies and tax exemption):

Mr. Wardropper said yesterday that there had been a debate within the Met about that [non-photographing] policy, which might be interpreted as simply a desire for the museumgoing public to forget that accidents sometimes happen, even at the Met. [Yup: damage control. ed.]

But he said it stemmed from two convictions on his part, one of them practical: that conservators working on the project within and outside the Met would feel unduly pressured and be subject to too much unwanted advice from conservators if the process were more public. “We just wanted to have a controlled dialogue regarding this,” he said.

The other, even stronger, conviction was philosophical — or perhaps emotional.

“Once you see a picture of a car accident, it just stays in your mind,” he said. “I was afraid that if we showed the fragments, then people would only remember the fragments and not see the whole piece.” He added, “There’s just something horrific about seeing a broken artwork.”

The “undue pressure” can actually be legitimate. I recall a watercolor book which, when photographed by a staff member before treatment, had all its colors boosted considerably by the digital camera (we didn’t use color charts in the margins). The post-treatment book came back looking very faded but the conservator’s own before/after slides proved that our photos were way-off, and had screwed up everyone’s expectations. It was also upsetting to the conservator, who was put on the spot wrongly.

The article merely alludes to the differences between conservation of sculpture versus canvases. This might have been developed by Kennedy, or might be something for a follow-up.

And on the day before the Kennedy piece appeared (Jan 26), the very talented ex-tabloid writer, Jim Dwyer, wrote in the Times’s “About New York” column a wonderful Aiiiiiiieee! piece on awful missteps in art. These sort of articles are like car accidents or slasher movies: you’re so happy it’s not happening to you: the paintings discarded with the packing crates, a shredded Lucien Freud, shattered Qing vases, the wrecking ball next door, the slipped elbow, and the piece de resistance (which Dwyer must be remembering from witnessing it), when Jean Kennedy Smith’s crystal was shattered. I confess that there’s a certain glee in the report cataloging horrible accidents–and I wonder if this isn’t Dwyer the populist tweaking the chi-chi art lovers. (At left: “Painting by Giorgio de Chirico… took a direct hit from a wrecking ball demolishing a building next door.”)

Oh, and the amusing thing with Dwyer: no museum would speak of misshaps in their own collection on the record. Dwyer does a nice job of conveying his own cynicism.

But there we have it: in libraries, we’re afraid to talk about disasters like thefts which suggest that we’re not careful curators of the world’s cultural heritage–that we’re not worthy of donations. Is there a similar element of that fear in museums, maybe under the rationalizations?

Maybe they’re right.

(Photos from the respective Times articles: 1-2 Metropolitan Museum, 2: Wolfgang v. Brauchitsc.)